Posts

Wiki Contributions

Comments

Ah, that makes sense! Well, it does seem to work out for some businesses, in particular East Asian business conglomerates. Let me quote from a common cog article on the topic of near every company having an equillibrium point past which further growth is difficult w/o a line of capital.

Chinese businessmen and the SME Loop

With a few notable exceptions, the vast majority of successful traditional Chinese businessmen have chosen the route of escaping the SME loop by pursuing additional — and completely different — lines of businesses. This has led to the prevalence of ‘Asian conglomerates’ — where a parent holding company owns many subsidiaries in an incredibly diverse number of industries: energy, edible oils, shipping, real estate, hospitality, telecommunications and so on. The benefit of this structure has been to subsidise new business units with the profits of other business units.

Why a majority of Chinese businessmen chose this route remains a major source of mystery for me. When I left the point-of-sale business in late 2017, I wondered what steps my boss would take to escape the SME loop. And I began to wonder if the first generation of traditional Chinese businessmen chose the route of multiple diversified businesses because it was the easiest way to escape the SME loop ... or if perhaps there was something about developing markets that caused them to expand this way.

(And if so, why are there less such conglomerates in the West? Why are these conglomerates far more common in Asia? These are interesting questions — but the answers aren’t readily available to me; not for a few decades, and not until I’ve have had the experience of growing such businesses.)

Perhaps the right way to think about this is that the relentless pursuit of growth led them to expand into adjacent markets — and the markets for commodities and infrastructure was ripe for the taking in the early years of South East Asia’s development.

Here, we see that chinese businessmen expand to keep up their free cash flow to fund their attempts to innovate enough to keep growing to larger scales.

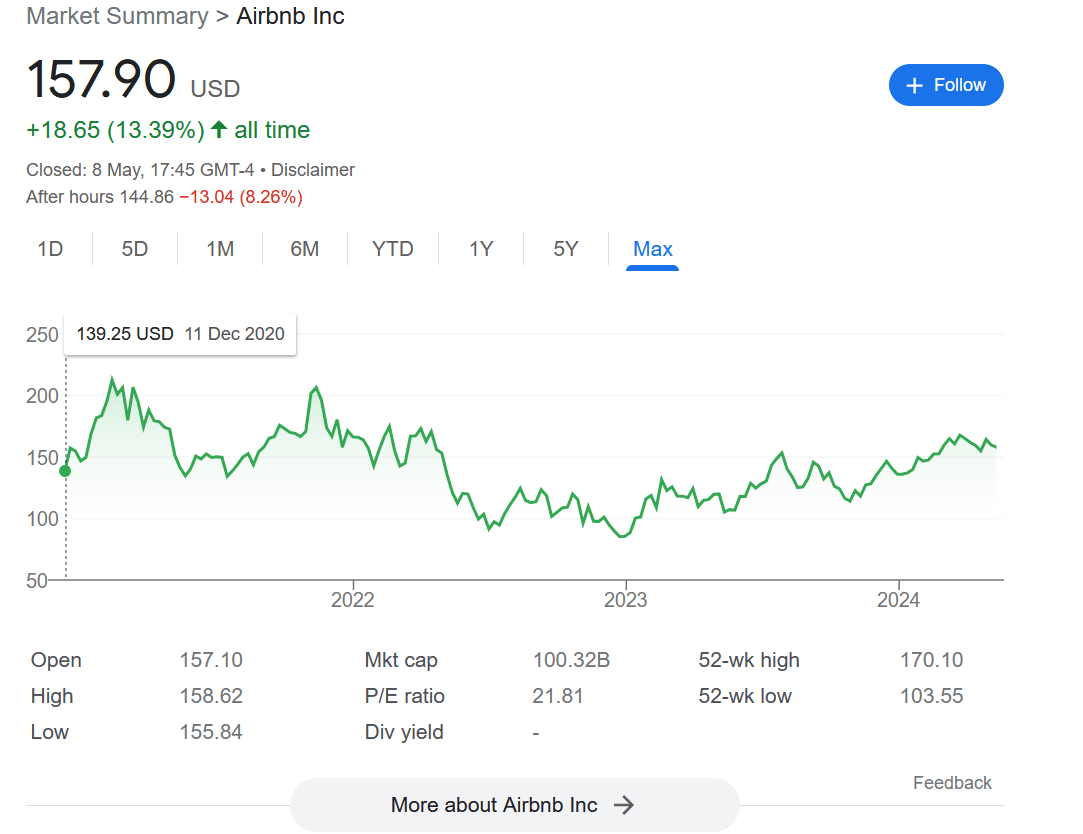

Uh, Brian did cut out a great deal of fat from AirBnB and the company clearly survived its brush with death due to Covid19. So I don't see why you'd say it didn't work.

Brian Chesky, a co-founder of AirBnB, claimed that their company did get bloated and they lost focus before Covid happened and they had to cut the fat or die. And he claimed this error is common amongst late-state startups. From "The Social Radars: Brian Chesky, Co-Founder & CEO of Airbnb (Part II)". So I think turning into an octupus is something that happens to succesful startups, and is probably what's happening to Dropbox.

Even though I think the comment was useful, it doesn't look to me like it was as useful as the typical 139 karma comment as I expect LW readers to be fairly unlikely to start popping benzos after reading this post. IMO it should've gotten like 30-40 karma. Even 60 wouldn't have been too shocking to me. But 139? That's way more karma than anything else I've posted.

I don't think it warrants this much karma, and I now share @ryan_greenblatt's concerns about the ability to vote on Quick Takes and Popular Comments introducing algorithmic virality to LW. That sort of thing is typically corrosive to epistemic hygeine as it changes the incentives of commenting more towards posting applause-lights. I don't think that's a good change for LW, as I think we've got too much group-think as it is.

I think you should write it. It sounds funny and a bunch of people have been calling out what they see as bad arguements that alginment is hard lately e.g. TurnTrout, QuintinPope, ZackMDavis, and karma wise they did fairly well.

@habryka this comment has an anomalous amount of karma. It showed up on popular comments, I think, and I'm wondering if people liked the comment when they saw it there which lead to a feedback loop of more eyeballs on the comment, more likes, more eyeball etc. If so, is that the intended behaviour of the popular comments feature? It seems like it shouldn't be.

Good point. I grabbed the dataset of gdp per capita vs life expectancy for almost all nations from OurWorldInData, log transformed GDP per capita and got a correlation of 0.85.

Although GDP per capita is distinct from this expanded welfare metric, the correlation between GDP per capita and this expanded welfare metric is very strong at 0.96, though there is substantial variation across countries, and welfare is more dispersed (standard deviation of 1.51 in logs) than is income (standard deviation of 1.27 in logs).[9]

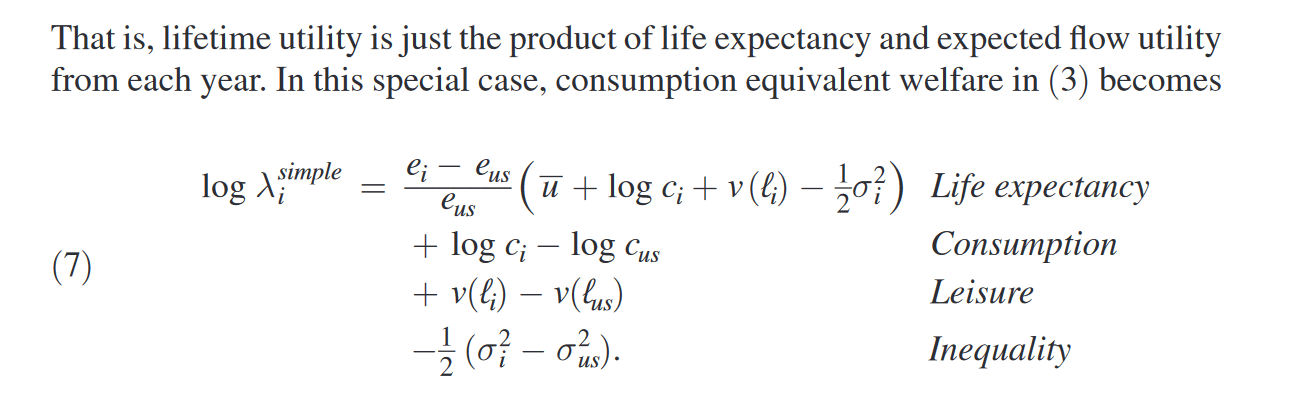

I checked the paper and it looks like they're comparing welfare by "how much more would person X from the US have to consume to move to another country i?" Which results in equations like this:

which says what the factor , should be in terms of differences in life expectancy, consumption, lessure and inequality. So I suppose it isn't suprising that it's quite correlated with GDP, given the individual correlations at play here, but I am suprised that it is so strongly correlated since I'd expect e.g. life expectancy vs gdp to correlate at maybe 0.8[1]. Which is a fair bit weaker than a 0.96 correlation!

This looks cool and I want to read it in detail, but I'd like to push back a bit against an implicit take that I thought was present here: namely, that GDP takes into account major technological breakthroughs. Let me just quote some text from this article: What Do GDP Growth Curves Really Mean?

More generally: when the price of a good falls a lot, that good is downweighted (proportional to its price drop) in real GDP calculations at end-of-period prices.

… and the way we calculate real GDP in practice is to use prices from a relatively recent year. We even move the reference year forward from time to time, so that it’s always near the end of the period when looking at long-term growth.

Real GDP Mainly Measures The Goods Which Are Revolutionized Least

Now let’s go back to our puzzle about growth since 1960, and electronics in particular.

The cost of a transistor has dropped by a stupidly huge amount since 1960 - I don’t have the data on hand, but let’s be conservative and call it a factor of 10^12 (i.e. a trillion). If we measure in 1960 prices, the transistors on a single modern chip would be worth billions. But instead we measure using recent prices, so the transistors on a single modern chip are worth… about as much as a single modern chip currently costs. And all the world’s transistors in 1960 were worth basically-zero.

1960 real GDP (and 1970 real GDP, and 1980 real GDP, etc) calculated at recent prices is dominated by the things which are expensive today - like real estate, for instance. Things which are cheap today are ignored in hindsight, even if they were a very big deal at the time.

In other words: real GDP growth mostly tracks production of goods which aren’t revolutionized. Goods whose prices drop dramatically are downweighted to near-zero, in hindsight.

When we see slow, mostly-steady real GDP growth curves, that mostly tells us about the slow and steady increase in production of things which haven’t been revolutionized. It tells us approximately-nothing about the huge revolutions in e.g. electronics.

John Carmack is a famously honest man. To illustrate this, I'll give you two stories. When Carmack was a kid, he desperately wanted the macs in his schools computer lab. So he and a buddy tried to steal some. They got caught because Carmack's friend was too fat to get through the window. Carmack went to juvie. When the counselor asked him if he wouldn't get caught, would he do it again? Carmack answered yes for this counterfactual.

Later, when working as a young developer, Carmack and his fellow employees would take the company workstations home to code games over the weekend. Their boss eventually noticed this and wondered if they were borrowing company property without permission. He quickly hit on a foolproof plan to catch them: just ask Carmack because he cannot tell a lie. Carmack said yes.

These stories aren't really a response to your point. I just find them to be hilarious examples of the inability to lie. They're also an existence proof of someone being unable to lie but still doing very well.